NO RIGHTS RETAINED

ROMOLAND: a pictonovel,

by Ben Stoltzfus and Judith Palmer

ROMOLAND is innovative, ironic, comic and playful. It is a postmodern event conjoining Judith Palmer, a feminist artist, and Ben Stoltzfus, a novelist. The written text uses 25 art works as generative surfaces for a series of dialogues between a man and a woman. The pictures and the text explore the historical subjection of women by men, their deliverance through art and the dismantling of cultural codes. Both texts foreground the voice of the Other as it manifests itself in the traces, lines and cracks of speech, be they visual or verbal. The arabesques of the woman’s sensibilities oppose the squares of man’s authority. Her art speaks and his text sees. Together, they unveil another space between the pictures and the text — the body of bliss and equality.

Author Bio

BEN STOLTZFUS is a novelist, translator and literary critic. He has received many grants and awards: Fulbright, Camargo, Humanities, Creative Arts, and in 1997, the Gradiva Award from NAAP for Lacan and Literature: Purloined Pretexts. He translated Alain Robbe-Grillet’s pictonovel, La Belle Captive, in collaboration with René Magritte, and The Target, a short fiction, in collaboration with Jasper Johns. Stoltzfus’ latest novel, Cat O’Nine Tails, was published in 2012. His study of Hemingway and French Writers appeared in 2010, and Magritte and Literature: Elective Affinities in 2013. He lives with his artist wife, Judith Palmer, in Riverside, California.

Artist Bio

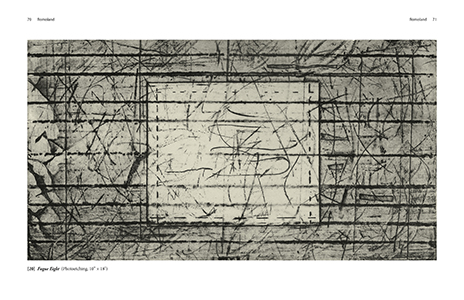

JUDITH PALMER is a printmaker whose work is in the tradition of Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, and Richard Diebenkorn. She explores the language of art and the process by which art’s sign-system communicates its message—line, texture, color and image. Palmer collects “found language”—numerals, words, sentences—from streets, walls or waste paper and transfers their photo images onto zinc plates. She combines these elements with traditional, more rigid patterns and techniques of etching. The result is a dialectic, a movement back and forth between spontaneously flowing arabesques that represent energy, aggression and rebellion, and the rigid, straight lines of confinement and restriction. Form becomes content.

Advance Praise for ROMOLAND: a pictonovel

This playful yet serious encounter between a woman’s images and a man’s text, ironically reflected within both the pictures and the words offers a gendered struggle between the linear and the arabesque, geometry and finesse, tradition and revolution that dramatizes the story of postmodern art and fiction with a feminist twist. A veritable tour de force that displays as it narrates, this picto-novel will shatter and renew the reader/viewer’s perception of the human condition. ( Wel)come to the blissful spacetime of Romoland.

— Roch C. Smith, Professor Emeritus of French at UNC-Greensboro

ROMOLAND is an amazing collaboration between two artists: a woman and a man, a wife and a husband. The woman’s visual strategy, in conjunction with the man’s witty “ecofeminist” text, plots the liberation of women—persistently and playfully. Her art speaks and his text sees, and the two together create a new reality: another “space of our own”—ROMOLAND.

— Ai Ogasawara, Associate Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan

“She inscribes the body of form and the inside of surface.” This compact phrase from Palmer and Stoltzfus’ Romoland elegantly captures for me the deceptively calm de(con)struction veiling the remarkable revolution taking place in this delightful work. Here, received ideas about the separate domains of masculine and feminine, inner and outer, line and mass, visual and narrative art, ruler and ruled, master and servant are playfully and seriously inverted to reveal that our unconscious sexual coding of space, time and form is coming undone. At last. A necessary undoing if we are to face what may and should comenext. Palmer’s artwork in Romoland is an indelible tracing of a double trajectory—of becoming-woman and becoming artist, breaching, incorporating, contesting and finally enveloping man’s “lines” (linguistic, visual, formal) in her pieces. Already in the series’ first woodcut, Body of the Text 5, the mythical first woman fully captured by the man—Echo—manages, with her right hand, to break into (or out of) her enclosure. The successive works in Romoland—constructions, proofs, assemblages, liberations, flights, fugues, are punctuated by moments of immobilization (Stasis Two) but even in an arrested condition the woman explodes with the riot of colors virtually ruled out by the man’s brown and cream palette. Punctuated, as well by moments of near equation, something like connection, somewhere on the verge of balance. Inscription 3: “Both bodies are on stage where he explores her language even as she repudiates his, or tries to.” She captures him in her frame, but also with her, having activated in her art “the space between his lines” (Fugue Two).

— Juliet Flower MacCannell, author of The Hysteric’s Guide to the Future Female Subject

Sample pages from ROMOLAND: a pictonovel

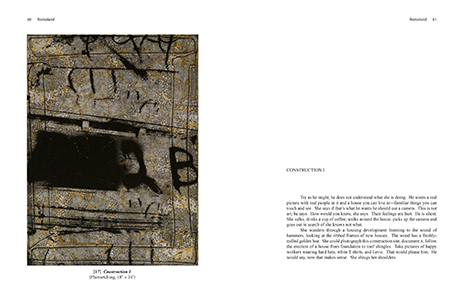

Romoland, pp 60-61

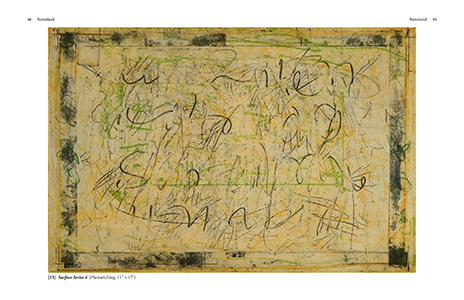

Romoland, pp 48-49

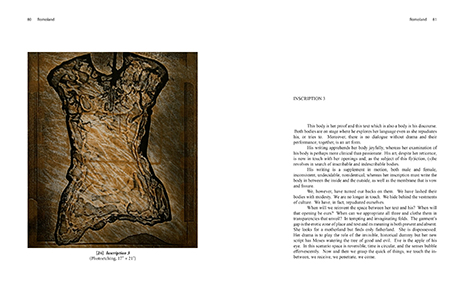

Romoland, pp 80-81

Romoland, pp 2-3

Halvor Aakhus © 2022